Abstract

This study investigated the feasibility of a teacher implemented intervention to accelerate phonological awareness, letter, and vocabulary knowledge in 141 children (mean age 5 years, 4 months) who entered school with lower levels of oral language ability. The children attended schools in low socioeconomic communities where additional stress was still evident 6 years after the devastating earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2011. The teachers implemented the intervention at the class or large group level for 20 h (four 30-min sessions per week for 10 weeks). A stepped wedge research design was used to evaluate intervention effects. Children with lower oral language ability made significantly more progress in both their phonological awareness and targeted vocabulary knowledge when the teachers implemented the intervention compared to progress made when teachers implemented their usual literacy curriculum. Importantly, the intervention accelerated children’s ability to use improved phonological awareness skills when decoding novel words (treatment effect size d = 0.88). Boys responded to the intervention as well as girls and the skills of children who identified as Māori or Pacific Islands (45.5% of the cohort) improved in similar ways to children who identified as New Zealand European. The findings have important implications for designing successful teacher-implemented interventions, within a multi-tier approach, to support children who enter school with known challenges for their literacy learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well established that children who enter school with lower levels of oral language are at risk for persistent literacy difficulties, particularly when they are from impoverished backgrounds (Aram, Ekelman, & Nation, 1984; Buckingham, Beaman, & Wheldall, 2014; Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomblin, 2001; Johnson, Beitchman, & Brownlie, 2010; Law, Rush, Schoon, & Parsons, 2009; Snowling, Duff, Nash, & Hulme, 2016; Stoeckel et al., 2013). What is not well understood, however, is how these children respond to early literacy instruction specifically designed to mitigate this risk. In particular, it is unclear whether class level interventions are effective in accelerating these children’s foundational literacy skills to an extent that can be transferred to the reading and writing processes (Carson, Gillon, & Boustead, 2013). The concept of “accelerated learning” is important given that an early gap between good and poor readers typically persists or increases over time (Billard et al., 2010; Cunningham & Stanovich, 1997) leading to inequities in educational, health and economic outcomes (Law et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2010). However, specific interventions (Dietrichson, Bog, Filges, & Jorgensen, 2017) as well as strong support systems such as family, cultural and community support (Macfarlane, Clarke, & Macfarlane, 2016) can potentially overcome disadvantage. Examining facilitators of early successful reading and writing experiences may help ensure more positive learning trajectories and life outcomes for these young children.

Many children with lower levels of oral language ability will not qualify for speech-language therapy or specialist learning support so teacher implemented intervention may be the only intervention they receive. It is critical, therefore, to understand the impact of teacher-led instruction on their literacy learning needs (Swanson et al., 2017). This study focused on children’s response to a 10-week class (or large group) intervention implemented by the class teacher. The intervention included adapted activities and strategies in phonological awareness, letter knowledge, and oral vocabulary that have proven effective for children with speech and language difficulties in previous experimental studies. The phonological awareness activities were adapted from the researchers’ previous intervention trials (Carson et al., 2013; Gillon, 2000, 2005; Gillon et al., 2007; McNeill, Gillon, & Dodd, 2009), and the vocabulary activities were based on a recent vocabulary intervention study (Marulis & Neuman, 2013) and the work of Justice, Meier, & Walpole (2005). The study was conducted in schools in low socioeconomic communities where children were raised in conditions that created additional stress for their early learning. Their community was significantly impacted by a series of devastating earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand. The children in this study (aged 5 or 6 years at study commencement) were born in the year of the major earthquake (2011) or the following year when significant after-shocks continued. Tragically, the February 22nd 2011 earthquake resulted in 185 deaths in the city and left many with serious long term physical injuries. Increased mental health problems in adults and increased behavioural problems in children have also been associated with this period (Fergusson, Horwood, Boden, & Mulder, 2014; Liberty, Tarren-Sweeney, Macfarlane, Basu, & Reid, 2016).

Raising early literacy achievement for children who enter school with known challenges to their learning ultimately requires a whole of system approach. Reading comprehension models highlight the importance of positive cognitive, psychological, and ecological factors to children’s reading achievement (Aaron, Joshi, Gooden, & Bentum, 2008). It is necessary to enhance factors within each of these domains to ensure better outcomes for children most in need. The current study is part of a 10-year programme of research which is examining the braiding of multiple influences on children’s early literacy and learning success (A Better Start, 2015–2024).

Children’s cognitive skills, however, have a direct influence on early reading and writing development (Tunmer & Chapman, 2012) and therefore have received particular attention in the research literature. Analyses from a longitudinal population birth cohort study in the United Kingdom (Russell, Ukoumunne, Ryder, Golding, & Norwich, 2018) where policy and early education curriculum changes have been specifically implemented to mitigate barriers to children’s literacy learning, showed the persistent influence of common risk factors in predicting children’s reading outcomes at 7 years of age (e.g., pre term birth, male gender, maternal level of education, social housing context, concerns with early speech and language development, parenting influences and child’s vocabulary development p. 58). These findings support the need for a whole of system approach to improve reading outcomes for children at high risk. However, the researchers also found that children’s phonological awareness ability at 4 or 5 years of age was a strong mediator of reading ability at 7 years of age. For example, 89% of the association between gender and word reading could be explained by performance on the phonological awareness measure. Phonological awareness skills mediated other predictors in the range of 52–64%.

Russell et al’s (2018) data are consistent with a wealth of research evidence. Findings from across different languages have consistently supported the powerful influence of phonological awareness, letter knowledge, and access to quality phonological representations in children’s early reading and spelling development (for reviews see Gillon, 2018; Hulme & Snowling, 2013; Moll et al., 2014). The critical importance of phonological awareness to children’s reading comprehension ability is via its role in developing efficient word reading skills. Other cognitive and oral language skills, particularly, semantic skills, are also important for reading (Nation & Snowling, 2004). Children’s vocabulary knowledge at 5 years of age may directly influence later reading comprehension ability and indirectly influence word decoding and word recognition skills (Tunmer & Chapman, 2012).

Vocabulary knowledge may also have a direct influence in supporting children’s ability to integrate information in the comprehension of written text (Perfetti & Stafura, 2014) and in understanding inferences from written text (Cain & Oakhill, 2014). Having a deeper understanding of a word’s meaning (vocabulary depth) may be more important than vocabulary breadth (number of words known) in children’s ability to make global cohesion inferences (inferences that require the integration of world knowledge (Cain & Oakhill, 2015). Grimm, Solari and Gerber (2018) found that the English receptive vocabulary knowledge of 5 year-old children, who were emerging bilingual (Spanish L1, English L2) and received literacy instruction in English, predicted their later reading comprehension in English (in 3rd grade and in 8th grade). This finding supports the need for early vocabulary instruction in the language of literacy instruction. However, the researchers also found a modest effect size of Spanish receptive vocabulary knowledge on 3rd grade reading comprehension in English, supporting the value of encouraging the continued development of children’s home language when different from the language of literacy instruction. Translating experimental research findings in phonological awareness and vocabulary development into cost effective interventions in real world settings is key in bringing about the systematic change that is necessary to raise literacy achievement for children at risk of literacy difficulties.

In New Zealand, children are typically identified for literacy intervention at the end of their first year of school with the support commencing in their second schooling year. The intervention provided is usually the Reading Recovery programme (Reading Recovery New Zealand, 2018). The rationale for investigating a change to this model and intervening from the outset of formal literacy instruction for children who enter school with lower levels of oral language ability is supported by the research evidence from multiple perspectives, including:

-

1.

Many children with lower levels of oral language may have multiple challenges to learning. In the current study, the children were living in low socioeconomic areas with additional community stress due to the earthquakes. For example, many families in the community either lost their homes, or had significant disruptions to their accommodation situation due to housing costs and repairs, some of which were ongoing at the time of the study. Gomez and Yoshikawa (2017) examined the oral language and early literacy skills of preschool children who experienced the strong earthquake in Santiago Chile, February 27, 2010 and over 1000 aftershocks. They found on average these children performed lower on letter knowledge and comprehension tasks than their peers who were evaluated on the same measures prior to the earthquakes. There was a relationship between the parents’ reported stressors following the earthquake and their children’s early literacy skills, highlighting a potential need to more pro-actively support children’s early literacy development in families experiencing ongoing stress post disaster. While natural disasters, such as earthquakes pose unique challenges, other conditions of stress create similar barriers to children’s language and literacy learning such as being raised in poverty (Wamba, 2010) or family social risk (Foster, Lambert, Abbott-Shim, McCarty, & Franze, 2005).

-

2.

Waiting to identify children who fall behind their peers in literacy achievement measures before intervening may negatively impact these children’s perception of themselves as a learner and their motivation to engage in reading. Morgan, Fuchs, Compton, Cordray, and Fuchs (2008) demonstrated that the relationship between children’s reading ability and their motivation to read emerges early (half way through their first year at school). Chapman, Tunmer and Prochnow (2000) found the relationship between children’s academic self-perception and reading performance also emerges early. Towards the end of their first year at school, children’s reading performance predicted whether they had either positive or negative academic self-perception with over 70% accuracy. McArthur, Castles, Kohnen, and Banales (2016) reported that poor readers who also had poor foundational oral language skills were at particular risk for lower general self-concept and lower academic self-concept.

-

3.

There is strong theoretical support from models of skilled reading to focus on foundational oral language skills early in children’s literacy development. The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Hoover & Gough, 1990) is a well-established model of reading comprehension which highlights the importance of both word decoding skills and linguistic comprehension to the ability to comprehend written text. The model has been validated via research findings in English (e.g., Catts, Adlof, & Weismer, 2006) and in transparent languages like Finnish (Torppa et al., 2016). Within the Simple View of Reading, phonological awareness, letter knowledge and rapid naming are robust predictors of efficient word decoding, and reading comprehension ability. In turn, early word decoding and linguistic comprehension ability predicts later reading comprehension. That is; the link between phonological awareness and letter knowledge to reading comprehension in later grades is mediated by their reading ability in Grade 1 (Torppa et al., 2016).

There is a need, then, to consider more pro-active intervention models that incorporate evidenced based literacy instruction in children’s first year of school to ensure reading success for children who enter school with lower foundational literacy skills (Tunmer & Chapman, 2015). Interventions in the first year at school will promote a more strengths based approach to children’s literacy learning (a move away from a ‘wait to fail’ approach) and foster positive learner self-concepts from the outset of literacy instruction. Numerous intervention studies have focused on facilitating literacy learning in younger children with lower levels of oral language skills. Most controlled intervention studies however, have targeted cognitive skills individually (e.g., phonological awareness interventions or vocabulary interventions). The majority of studies have also utilized a small group or individual intervention format which was implemented by researchers, speech-language therapists, or trained assistants (e.g., see Al Otaiba, Puranik, Ziolkowski, & Montgomery, 2009). Wake et al.’s study (2013) was one attempt to examine the long term outcomes of an intervention that concurrently targeted oral language and phonological awareness. The large scale controlled intervention study included preschool children with speech-language impairment. Trained assistants implemented 18 individual sessions in the home to improve oral language (vocabulary, narrative and grammar) and phonological awareness. Significant longer term treatment effects (at 6 years of age) were evident in phonological awareness alone. The authors questioned, however, whether a similar intervention effect in phonological awareness could be obtained through a less intensive intervention model.

Large group or class level interventions potentially provide an efficient way to advance literacy skills for children at higher risk as a first step within a multitier intervention approach (Swanson et al., 2017). It is important, however, to carefully examine how children with lower levels of oral language respond to class based interventions. Carson et al. (2013) reported that although the class level phonological awareness programme was effective in significantly increasing reading performance for most 5 year old children, those with oral language difficulties struggled to transfer their improved phonological awareness ability to the reading and spelling process. The current study advances this research through increasing the focus in the intervention on children’s ability to use improved phonological awareness skills in word reading and spelling activities.

Class-level interventions involve diverse groups of children. Understanding whether girls respond differently to boys and whether interventions are culturally responsive to children from diverse backgrounds are areas that require investigation. Data from the Progress in International Literacy Study, PIRLS (Mullis, Martin, Foy, & Hooper, 2017) for 10–11 year old children has consistently shown that girls out-perform boys and that higher reading achievement is associated with economic advantage. In New Zealand, where the current study is based, the difference between boys’ and girls’ performance within the PIRLS is larger than the international average. In a recent study, Schluter et al. (2018) analysed health and literacy intervention data from over 255,000 New Zealand children that was available through the Statistics New Zealand Integrated Data Infrastructure (Statistics New Zealand, 2017). Boys had a 65% higher risk of receiving a literacy intervention than girls, and children in the most deprived economic areas had a 62% higher risk for literacy intervention. Males who identified as Māori or Pasifika, from rural areas, or areas of high deprivation were the most likely to receive a literacy intervention.

There are a range of factors to consider in understanding gender, cultural and economic differences in early literacy outcomes (including assessment measures used, motivational factors, or cultural biases) but understanding the response of different groups to class instruction focused on foundational literacy skills will help elucidate the potential need to better adapt to differences.

The current study aimed to investigate the feasibility of teacher-led intervention designed to accelerate phonological awareness, letter knowledge, and vocabulary knowledge for 5–6 year-old children with lower oral language ability and who are living in communities that create multiple challenges to successful learning.

Research questions asked were:

-

1.

Does specific and explicit teaching in phonological awareness, letter knowledge and vocabulary, implemented by the class teacher, accelerate learning of children with lower levels of oral language ability compared to regular literacy curriculum?

-

2.

Does specific and explicit teaching in phonological awareness, letter knowledge and vocabulary, set within a culturally responsive framework, advantage or disadvantage any particular cultural group and do boys and girls respond to the teaching in similar ways?

Method

Participant selection

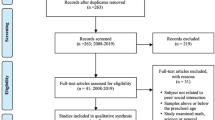

Seven schools in two lower socioeconomic communities in Christchurch, New Zealand, that were significantly impacted by the 2011 Christchurch earthquake were invited to participate in the study with all agreeing. Children in their first year at school from these seven schools whose parents consented (n = 247) were screened for their language skill in English using the Recalling sentences subtest of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals Preschool—Second Edition-Australian and New Zealand Edition (CELF-P2; Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2006) and the initial phoneme identity subtest of the Computer Based Phonological Awareness Assessment (CBPA; Carson, Gillon, & Boustead, 2011). Lower levels of oral language was operationally defined in the study as a scaled score of 7 or below on the recalling sentences subtest and/or a raw score of 5 or below on the initial phoneme identity subtest. These criteria were selected to identify children with below average performance in one or both of these key areas supporting early literacy development based on normative data and previous studies examined the predictive utility of the CBPA (Carson et al., 2011; Semel et al., 2006).

Following this screening assessment, 152 (61.5%) were identified as having lower levels of oral language according to the criteria described above and received an in-depth oral language assessment. Due to some children leaving the area after study commencement, full data sets were available for 141 of these children (70 boys, 71 girls; mean age = 5.4 years (64.6 months; SD = 3.3 m). The ethnicity of this cohort was: New Zealand European (41.3%), Māori (24.5%), Pasifika (21.0%) Filipino (6.3%), and Other (6.9%). There were 29 children (i.e., 20.6%) who spoke English and another language. In addition to oral language assessment, 51 children were referred for speech production assessment due to concerns regarding intelligibility. Mean performance on the phonology subtest of the Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology (DEAP; Dodd, Huo, Crosbie, Holm, & Ozanne, 2006) for this subgroup was 85.1 percent consonants correct (SD = 11.4). Children who passed the screening assessment (i.e., did not show evidence of oral language weakness) participated in the class-wide intervention, but their detailed response to the programme was not monitored in the current study).

In New Zealand, each school is assigned a decile ranking from 1 to 10 that indicates the socioeconomic level of the community in which it is located (1 = lowest level). Schools in this study had been assigned a decile ranking of 1–3, indicating low socioeconomic communities according to national census data (Ministry of Education, 2011). The seven participating schools were placed into either Group A (n = 3 schools) or Group B (n = 4 schools) based on teacher availability for pre-intervention workshop participation.

Procedure

A stepped wedge research design (Fok, Henry, & Allen, 2015) was utilized to examine the intervention effects for children with lower levels of oral language where the intervention was rolled out sequentially in Group A (72 children across 3 schools) and then Group B (69 children across 4 schools) following a baseline monitoring phase. In New Zealand, the school year is divided into four teaching terms of 10 weeks in duration. Following the assessment and baseline phase in School Term 1 for all children, Group A children received the intervention in School Term 2 and Group B children received the intervention in School Term 3.

Professional learning for teachers

Across the seven schools there were 22 classes of children in Year 1 (10 classes in the Group A and 12 classes in Group B) with an average of 14.1 (SD = 4.2) children per class. The teachers from these classes participated in professional learning which comprised:

Workshop participation

Teachers participated in one half day and one full day workshop in the term immediately preceding the implementation of the research intervention. Workshop content focused on the research evidence base to support explicit teaching of phonological awareness and vocabulary teaching and co-constructing elements of the proposed intervention lesson plans with the teachers. For example, optimizing the complexity of the content targeted within lessons, problem solving through logistical constraints around class size and timetabling, receiving feedback regarding intervention activities.

On-line learning support

Teachers had access to an online learning environment through a website. The website included five professional development modules focused on the assessment and teaching of phonological awareness in the classroom context and included video demonstration of activities within the intervention. The platform was also used as a vehicle to collect intervention fidelity checks (further detail below), allow discussion amongst teachers and queries to be sent to the research team.

In-class support

The third component of the professional learning was the provision of support within the classroom context during the intervention period. All teachers had at least one session modelled by a member of the research team in their classroom and Ministry of Education speech-language therapists also offered support. On average, about 12 h of support was provided to each teacher over the 10 week intervention period.

Assessment

Assessment measures were administered by a member of the research team or speech language therapists who were familiar with the assessment protocol. The assessment was conducted in three 30-min sessions on separate days. The assessment sessions were conducted in a quiet space in the child’s school and were audio recorded for accuracy and reliability purposes.

The following subtests of the CELF-P2 (Semel et al., 2006) were administered: word structures, expressive vocabulary, recalling sentences (administered during the screening assessment) and sentence structure. Raw scores and scaled scores (a score of 7–13 indicates performance in the expected range for a child’s age) were collected for analysis. The CELF has good psychometric properties. Test–retest reliability coefficients range from 0.78 to 0.90 and internal consistency ranges from 0.80 to 0.96 across subtests.

The following measures were administered to all participants at three assessment points: Time 1 (in school term 1 prior to intervention), Time 2 (end of school term 2 when Group A children had received the intervention), and Time 3 (end of school term 3 when Group B children had received the intervention). Children were not trained during the intervention on the phonological awareness or non-word reading items to allow for assessment trials to measure transfer knowledge to novel words.

-

1.

Phonological awareness was evaluated using the Computer Based Phonological Awareness Assessment Tool (CBPAT) (Carson et al., 2011). The CBPAT has good psychometric properties. Test–retest reliability coefficents are .70 or above for all subtests (Carson et al., 2015). Raw scores were collected for all subtests. A combined phonological awareness score was collated from the following subtests.

-

a.

Initial phoneme identity: Children were asked to identify one out of three words that started with a target sound. (10 test items)

-

b.

Phoneme segmentation: Children were asked to identify the number of sounds in a target word. (18 test items, discontinued after four consecutive errors)

-

c.

Phoneme blending: Children were asked to blend sounds together to form a word and select the corresponding picture. (15 test items, discontinued after four consecutive errors)

-

a.

-

2.

Letter-sound knowledge (subtest from the CBAT): Children were asked to identify one letter out of 6 items that corresponded with a target sound. (18 test items, discontinued after six consecutive errors).

-

3.

Non-word reading (Calder, 1992): Children were asked to read 10 non-words (e.g., vab, zug). Two practice items were included to familiarise children with the tasks. The total number of graphemes (out of 30) read correctly was collected for analysis.

-

4.

Letter knowledge fluency (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, DIBELS; Good & Kaminski, 2002): Children named as many letters as possible in 1 min by reading a series of lower and upper case letters presented on a page. If the child did not know the name of a particular letter, the examiner provided the correct response and the child moved to the next item. Raw scores were collected for analysis.

-

5.

Vocabulary probes: Twenty tier 2 words (i.e., words that are not part of everyday social conversation but are general enough to be used across multiple topics) from the story books used in the intervention were selected for inclusion in an expressive vocabulary probe. Ten of these words were amongst the targeted words within the intervention through elaboration (i.e., teachers provided a definition during the story book reading and could create activities to reinforce children’s understanding of the item). A further 10 items were unelaborated (i.e., children were exposed to the words during the story book reading but they were not elaborated by teachers).

In the assessment probe, children were asked to “tell me what [item] means”, followed by “tell me anything about [item]?” if further prompting was required. Responses were recorded verbatim for later scoring by a trained research assistant using the protocol developed by Justice, Meier and Walpole (2005). Children received a score of 2 for complete knowledge, 1 for incomplete knowledge and 0 for no knowledge.

Following comprehensive assessment, all children identified through the screening assessment remained in the lower oral language group based on their CELF-P2 oral language and phoneme awareness performance.

Table 1 summarises the age, language and literacy skills of participants in Group A and Group B at the start of the school year. Speech scores (percent consonants correct) are also presented for the 51 children across groups (25 children in Group A and 26 children in Group B) who exhibited lower speech intelligibility during screening assessment. An independent samples t test was conducted to compare performance in key measures at baseline. There were no significant differences between groups.

Scoring reliability

Data was scored in real time by the examiners with 20% of each assessment task was re-scored using audio recordings. Inter-rater reliability for all measures was 100%.

Usual literacy curriculum

The teachers followed the New Zealand English curriculum framework achievement level 1. The curriculum is focused on listening, reading, viewing, speaking, writing and presenting. The curriculum includes performance indicators around children’s letter sound knowledge, their ability to use a range of cues such as meaning, structure, visual, grapho-phonic and prior knowledge to comprehend written text and in writing, their ability to recognize in print a large bank of high frequency words. Teachers are encouraged to shape the curriculum so that teaching and learning is meaningful for their particular students. Most of the teachers used commercial programs for phonological awareness and phonics activities. Teachers focused on the literacy curriculum for at least one teaching session daily.

Better Start Literacy Intervention

The Better Start Literacy Intervention was designed to support children’s phonological awareness, letter-sound knowledge and vocabulary growth within a culturally responsive paradigm in children’s first year of school. The intervention consisted of 4 × 30 min sessions over 10 weeks and this intervention replaced 30 min of the teacher’s usual literacy curriculum (typically replacing the teachers’ phonics, phonological awareness and shared book reading instruction). Children were introduced to a quality story book each week of the intervention and the phonological awareness and vocabulary instruction was built around story book. For example, in the week when ‘Down in the Forest’ (Morrison, 2004) was the story book focus, words associated with the forest such as tree, frog, bird, log, leaf, were target words in the phoneme identity, blending and segmentation games.

The phonological awareness component of the intervention was adapted from the original and classroom based versions of the Phonological Awareness Training Programme (PAT; Gillon, 2000; Carson et al., 2013). In line with effective principles of phonological awareness (Gillon, 2018), all activities were based at the phoneme level and letter-sound knowledge was integrated in the activities. Level l (easier) and Level 2 (harder) tasks were provided for the teacher to select activities that catered for diversity in the children’s abilities. Activities that provided children with supported opportunities to use their increasing phonological awareness knowledge in reading and writing attempts were included in each lesson.

The vocabulary component of the intervention was adapted from Justice et al. (2005). The storybook for the week was used as a context to increase vocabulary knowledge. Target tier two words in the story book for the week were pre-selected for elaboration. There were four targeted vocabulary items each week of the intervention. A sticker that provided an elaboration of each target word that the teacher could read verbatim was placed at the appropriate pages in the story book. Thus, children were exposed to the vocabulary item and its elaboration within the context of the story. On the first and third lesson in the week, the entire story book was read and targeted words were elaborated at the appropriate place in the story. On the second and fourth session in the week, teachers summarised the story and targeted words were elaborated at the appropriate place in the summary.

Cultural responsiveness was incorporated in the intervention by introducing the children and teachers to the Tātaiako competencies (Ministry of Education, 2017) as they related to the storylines in the weekly story book. In New Zealand, these competencies have been introduced to describe the behaviours of teachers who are able to know, respect and work with Māori learners and their families (Ministry of Education, 2017). The critical nature of understanding a child’s identity, language and culture embedded throughout the competencies are also relevant to support the learning of children from other cultural backgrounds (Gillon & Macfarlane, 2017). Within the context of the intervention, the introduction of the competencies (e.g., ‘manaakitanga’—showing integrity and respect) fulfilled the following aims: (1) Children were introduced to the meanings of these abstract words. (2) Their inclusion promoted children’s critical thinking by allowing them to begin to relate the competencies to the overarching theme of the story and to their own experiences. (3) The multisyllabic words provided a context for phonological awareness and pronunciation practice of Māori words by children and their teachers. (4) Reinforced the teachers’ knowledge of the competencies and supported their integration of these concepts into their teaching practices throughout the curriculum.

The components of a 30 min session started with a 5–7 min reading or summary of the book which included the elaboration of targeted vocabulary items. The start of the session was also used to discuss/review meaning of the Tātaiako competency for the week and relate it to the week’s book. The next 15–20 min was spent on phonological awareness activities that integrated letter-sound knowledge (i.e., phoneme identity, phoneme segmentation/blending and phoneme manipulation activities). The stimuli used in these tasks were related to the book and/or target sound for the week. The final 5–10 min was spent on transfer activities which required children to use a phonological strategy in a reading and/or writing task. For example, reading or spelling bingo, reading or spelling simple sentences containing a carrier phrase related to the book. Examples of the key phonological awareness activities are included in Table 2. The level of difficulty of the tasks was altered by using forced choice strategies (easier) or increasing the phonological complexity of the target word (harder).

Teachers were provided with detailed lesson plans, story books and phoneme awareness game resources for the first 8 weeks of the programme. A minimum number of items to be included in each phonological awareness and transfer activity was identified on the lesson plans to control intervention intensity across classrooms. In weeks 2–8, teachers were required to plan the fourth session in the week by repeating successful activities from the week or developing their own activities that incorporated the week’s target skills. The final 2 weeks of the programme were planned fully by the teachers, including selecting appropriate story books as a context for the intervention. Feedback regarding the independently planned lessons was provided to teachers before their implementation. The ultimate aim of this structure was to diminish teachers’ reliance on the structured lesson plans to ensure integration with other elements of the literacy programme.

Intervention fidelity

Teachers were required to complete an online checklist at the end of each week of the intervention. In the checklist, teachers reported on: (1) the level of engagement of the children during the session; (2) whether key components of the intervention were included (i.e., storybook reading, elaboration of targeted vocabulary, phoneme identity, phoneme segmentation, phoneme blending, phoneme manipulation with graphemes, reading/writing transfer task); (3) the total time that the lesson took. Twenty percent of logs were randomly selected to verify the key components were present in the lessons. Of the 46 logs reviewed, 44 (96%) included the key intervention components. Two teachers reported running out of time for the reading/writing transfer task. All teachers reported providing at least 30 min of teaching.

Teachers were also required to audio or video record their lessons. Ten percent of these recordings were randomly selected and reviewed by an independent assessor. Adherence to the key intervention components along with total minimum amount of instructional time (i.e., 30 min) were verified by the assessor. Key intervention components were verified for 100% of recordings whilst 92% of recordings included 30 min (± 5 min of instructional time).

Results

Impact of the intervention on phonological awareness, letter-sound knowledge and vocabulary knowledge

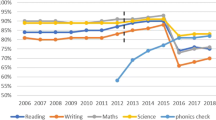

Group performances on measures of phonological awareness, letter-sound knowledge, letter knowledge fluency, non-word reading and vocabulary probes were compared at Time 1 (in school term 1 prior to intervention), Time 2 (end of school term 2 when Group A children had received the intervention), and Time 3 (end of school term 3 when Group B children had received the intervention). A multivariate approach to repeated measures (Assessment Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 × Group) was used to explore differences in the above measures over the intervention period. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used when the assumption of sphericity was violated for the interaction term as assessed by Mauchly’s test of sphericity (p > .05). Descriptive statistics showing mean performance by Group A and B at the three assessment points can be viewed in Table 3 and Non-word reading performance is depicted in Fig. 1.

Phonological awareness (PA)

There was a statistically significant interaction between intervention and time on phonological awareness, F(2, 278) = 5.190, p = .006. Univariate analysis showed that PA was not statistically significantly different in Group A compared to Group B at Time 1, F(1, 141) = 2.017 (p = .158, d = 0.24) or Time 3, F(1, 139) = 1.879 (p = .173, d = 0.23). Group A, however, significantly outperformed Group B in PA at Time 2 indicating a clear intervention effect, F(1, 141) = 11.408 (p = .001, d = 0.60). Group A and B showed statistically significant growth in PA across each time point (p < .001).

Letter-sound knowledge

There was no significant interaction between intervention and time on letter-sound knowledge, F(1, 826, 253.792) = 0.861 (p = .415). Group A and B showed statistically significant growth in letter-sound knowledge at each assessment point (p < .001) and a similar pattern of growth was present in response to the research intervention and routine classroom curriculum.

Letter-knowledge fluency

There was a statistically significant interaction between intervention and time on letter knowledge fluency, F(1.687, 232.832) = 10.615 (p < .001). Univariate analysis showed that letter knowledge fluency was not statistically different between Group A and Group B at Time 1 [F(1, 140) = 0.194 (p = .660, d = 0.1)] or Time 2 [F(1, 141) = 2.887 (p = .092, d = 0.29). However, Group A outperformed Group B at Time 3 [F(1, 139) = 6.265 (p = .013, d = 0.42). Evaluation of the effect of time showed that Group A and Group B showed significant growth across each time point (p < .001).

Vocabulary

There was a statistically significant interaction between intervention and time on vocabulary knowledge for elaborated words [F(1.812, 250.060) = 24.443 (p < .001)]. Univariate analysis showed that there was no difference in knowledge of elaborated words between groups at time 1 [F(1, 140) = 0.086 (p = .769, d = 0.05)]. Group A out-performed Group B in knowledge of elaborated words at time 2 [F(1, 141) = 5.650 (p = .019, d = 0.40)] whereas Group B out-performed Group A in knowledge of elaborated words at time 3 [F(1, 139) = 12.561 (p = .001, d = 0.61)]. There was a significant main effect of time for Group A [F(1.967, 137.717) = 32.177, p < .001)] and Group B [F(1.531, 104.089) = 82.603 (p < .001)]. Post-hoc testing (with Bonferroni correction) showed that Group A showed significantly higher scores at time 2 and time 3 compared to time 1 (p < .001). There was no significant difference in time 2 versus time 3 scores for Group A (p = .294). Group B showed no difference in scores between time 1 and time 2 (p = .186) and a difference between time 2 and time 3 scores (p < .001).

There was a statistically significant intervention between intervention and time on vocabulary knowledge for unelaborated words [F(2, 276) = 6.194 (p < .001)]. Univariate analysis showed that there was no difference in knowledge of unelaborated words between Group A and B at any assessment point (time 1 [F(1, 140) = 2.137 (p = .146, d = 0.25), time 2 [F(1, 141) = 2.232 (p = 0.137, d = 0.26), time 3 [F(1, 139) = 1.998 (p = .160, d = 0.24)]. There was a significant main effect of time for Group A [F(2, 140) = 25.080 (p < .001)] and Group B [F(2, 136) = 29.069 (p < .001). Post-hoc testing (with Bonferroni correction) for Group A showed that there was a significant difference between time 1 and time 2 (p < .001) and time 1 and time 3 (p < .001) and no difference between performance at time 2 and 3 (p = .399). Post-hoc testing (with Bonferroni correction) for Group B showed that was no difference between time 1 and time 2 performance (p = .801) and significant difference between time 2 and time 3 (p < .001) and time 1 and time 3 performance (p < .001).

Non-word reading (NWR)

There was a statistically significant interaction between intervention and time on NWR, F(1.863, 257.025) = 9.002 (p < .001). Univariate analysis showed that there was no difference in NWR performance in Group A and Group B at Time 1 [F(1, 140) = 3.108 (p = .080, d = 0.30)]. Group A outperformed Group B in NWR performance at Time 2 [F(1, 141) = 26.654 (p < .001, d = 0.88)] and Time 3 [F(1, 139) = 7.365 (p = .001, d = 0.46). Evaluation of the effect of time showed that Group A and Group B showed significant growth in non-word reading across each time point (p < .001). The growth in non-word reading across each assessment point is depicted in Fig. 1.

Impact of the Intervention on boys versus girls

A multivariate approach to repeated measures (Assessment Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 × gender) was used to explore differences in response to the intervention in boys and girls. There was no statistically significant interaction between gender and time on phonological awareness [F(2, 278) = 0.436 (p = .647)], letter knowledge fluency [F(1.733, 239.132) = 0.762 (p = .468)], non-word reading [F(1.909, 263.379) = 1.251 (p = .287)], elaborated vocabulary [F(1.889, 260.713) = 0.521 (p = .594)] and unelaborated vocabulary [F(2, 276) = 0.731 (p = .482)].

There was a statistically significant intervention between gender and time on letter-sound knowledge [F(1.835, 255.051) = 2.180 (p = .015)]. Univariate analysis showed that girls performed better than boys in letter-sound knowledge at time 1 [F(1, 141) = 6.314 (p = .013)]. There was no difference in letter-sound knowledge between boys and girls at time 2 [F(1, 141) = 0.811 (p = .369) and time 3 [F(1, 139) = 1.973 (p < .001)]. There was significant growth (p < .05) in letter sound knowledge across all three time points for girls and boys.

Impact of the intervention on different cultural groups

A multivariate approach to repeated measures (Assessment Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 × ethnicity) was used to explore differences in response to the intervention for children who identified as New Zealand European (n = 59), Māori (n = 36) and Pacific (n = 30) backgrounds. Children who were outside of these three main groups within the data set were excluded from the analysis.

There was no statistically significant interaction between ethnicity and time on phonological awareness [F(4, 240) = 0.227 (p = .923)], letter-sound knowledge [F(3.605, 216.301) = 0.428 (p = .789)] letter knowledge fluency [F(3.539, 210.585) = 0.197 (p = .923)], non-word reading [F(4, 238) = 0.370 (p = .830], elaborated vocabulary [F(3.733, 222.135) = 0.975 (p = .422)] and unelaborated vocabulary [F(4, 238) = 1.070 (p = .372)].

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of a class level intervention (referred to as the Better Start Literacy Intervention) in accelerating phonological awareness, letter knowledge and vocabulary knowledge in children who entered school with lower levels of oral language ability. The focus of the intervention was supporting children to learn to read in the complex English orthography. Participants attended schools in low socioeconomic communities which had experienced multiple challenges in the aftermath of the devastating earthquakes in their city. A stepped wedge research design was used to compare children’s performance when teachers implemented the Better Start Literacy Intervention for a minimum of 2 h per week over a 10-week teaching period compared to when teachers’ implemented their regular class literacy programme.

Data analyses demonstrated that the Better Start Literacy Intervention was significantly more effective in enhancing children’s phonological awareness and targeted vocabulary knowledge than the regular class curriculum, but that the regular curriculum was equally effective in developing children’s letter knowledge. Importantly, data analyses revealed that the children’s ability to use improved phonological skills to decode novel words improved to a significantly greater extent during the Better Start Literacy Intervention period compared to the usual classroom curriculum, with a large treatment effect (d = 0.88) evident for children’s non-word decoding ability.

Interestingly, the intervention had a cumulative benefit for word decoding ability as evidenced by the stronger performance over time for the children in Group A, who received the intervention first. This finding is consistent with a “self-teaching” process for reading development. The self-teaching hypothesis (Share, 1995) proposes that successful early word decoding attempts help young children establish orthographic representations in memory which they can then quickly access in future reading and spelling encounters. This provides them with an advantage for continued self-learning and helps to build their reading fluency and confidence. This finding supports the benefit of a targeted class intervention from school entry to develop the phonological awareness skills necessary for word decoding in children who enter school with lower levels of oral language.

Evidence of transfer of improved phonological awareness skills to word decoding for children with lower levels of oral language ability is encouraging since previous research has shown such children often struggle with transfer of skills (Carson et al., 2013). Key differences in the structure of the intervention may help explain the difference in transfer effects between these studies. Lesson plans within the Better Start Literacy Intervention included 5–10 min of each session on activities that required children to use a phonological strategy in a reading or writing task or phoneme manipulation with grapheme tracking activities. In Carson et al’s study, less intensity was focused on transfer activities as a hierarchical teaching approach from rhyme awareness, to easier and then harder phoneme awareness skills was adopted.

Findings reinforce the importance of ensuring that the content of phonological awareness programmes will best promote children’s literacy development. Enhanced phonological awareness skills are valuable only to the extent that they support children in their reading and spelling attempts. In this study children who received their usual literacy curriculum were exposed to phonological awareness activities and this was associated with improvement in their phonological awareness skills. However, the Better Start Literacy Intervention resulted in significantly greater improvement in phonological awareness skills and greater ability for children to use phonological awareness in decoding novel words. Phonological awareness activities that focus on complex phoneme awareness skills (phoneme segmentation, blending and manipulation) and make the link between speech and print explicit are recommended to promote reading and spelling development (Al Otaiba et al., 2009). In contrast programmes that predominantly target rhyme or syllable awareness skills, focus solely on initial phoneme awareness for school-aged children, and do not draw children’s attention directly to the link between spoken and written forms of a word appear to have limited benefits for reading or spelling (Nancollis, Lawrie, & Dodd, 2005). Although ongoing support would still be required for children in the current study with more significant language needs, advancing foundational literacy skills through class intervention allows for smaller group follow up intervention that focuses on more advanced skills. Therefore, the efficiency and cost effectiveness of additional interventions are potentially improved following the class programme.

The intervention structure of using a quality children’s story book containing more complex vocabulary was successful in extending children’s vocabulary knowledge. Findings were consistent with previous research showing that elaboration during shared book reading is a useful technique for advancing young children’s vocabulary development. Further, the technique is more effective than hearing the words in the story without elaboration.

Evidence of successful strategies that support teachers using more deliberate ways to increase children’s vocabulary and phonological awareness at the large group level is important in guiding practice. Interviews of teachers in the USA Head Start programme (O’Leary, Cockburn, Powell, & Diamond, 2010) revealed vocabulary and phonological awareness is commonly taught at the large group level and that there is wide variation in teaching practices. The researchers recommended that the importance of specific teaching strategies to improve both the breadth and depth of children’s vocabulary needed to be highlighted in the curriculum and that teachers would benefit from greater understanding of effective phonological awareness teaching as distinct from phonics teaching. A key component of the Better Start Literacy Intervention was providing professional development and ongoing support for teachers in their implementation of the programme alongside giving teachers increasing responsibility for lesson planning. If the intervention is utilised within other school settings, it is important to ensure that the same teacher support is provided so that similar intervention effects can be expected.

The lack of an intervention effect for letter-sound knowledge and letter knowledge fluency demonstrated that the usual literacy curriculum was effective in teaching children letter names and letter sounds for singleton consonants and vowels. The results suggest, however, that when letter-sound knowledge is combined with structured phonological awareness instruction that makes explicit for the children how to use phonological cues in decoding text (as provided in the Better Start Literacy Intervention) much greater gains in children’s word decoding ability can be realised. Given the lack of a specific intervention effect on letter-sound knowledge and fluency, it may also be advantageous to strengthen the focus on letter-sound knowledge within the intervention.

The success of the class teachers implementing the intervention is encouraging. Previous studies have highlighted the need for teachers to gain more in-depth knowledge about language structure, particularly in relation to phonological awareness skills (Carson & Bayetto, 2018; Moats, 2009). Although teachers’ phonological awareness knowledge was not measured prior to intervention, their participation in pre-intervention workshops, online learning modules as well as the support they received through the 10-week intervention period, appeared adequate to ensure the integrity of the instruction. However, the level of teacher support (on average 12 h over 10 weeks) was much greater than that typically received in supporting the early literacy development of children in their first year at school. Future studies should consider the longer term educational and economic benefits of this increased teacher support to promote early literacy development within disadvantaged communities.

The researchers valued the teachers’ feedback on aspects of study design and programme content. When undertaking research in classroom settings, teachers who know the abilities, interests and behaviours of their children may be best placed to provide input into practicalities of interventions. Feedback related to the length and topics of the stories selected, activities that worked well with larger groups of children, materials that supported teachers’ ability to adapt tasks to meet the needs of diverse learners, and the minimum number of trials spent on specific activities all helped to guide the development of the research intervention. This type of co-construction of interventions within classroom settings supports previous findings demonstrating advantages to children’s learning when teachers and speech-language therapists collaborate on intervention compared to speech language therapists working alone (Throneburg, Calvert, Sturm, Paramboukas, & Paul, 2000). However, the benefit of co-construction was not investigated as an experimental variable. There is a need for future research to directly compare different models of planning and delivery of class interventions in terms of improving outcomes for children’s language and literacy learning (Cirrin et al., 2010).

The finding that boys and girls, and children from different cultural groups showed a similar positive response to the intervention validates the potential usefulness of the intervention with diverse learners from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Follow up data is necessary to ascertain whether there are longer term benefits to children who receive the intervention.

Limitations

Undertaking intervention in regular school settings imposes natural challenges to research designs. Although the stepped wedge research design was chosen to mitigate some of these challenges, not all threats to data validity could be managed. The schools the children attended were not randomly assigned to the order of intervention. Rather teachers’ availability to attend the pre-intervention workshops (e.g., avoiding clashes with school events) determined the order for intervention. It was important for the teachers to receive the education workshops just prior to their class’s participation in the intervention. This helped ensure teachers did not introduce their new knowledge into class activities prior to their commencement of the intervention trial. Similarity in skills between children in Group A and Group B at pre-intervention suggested there was no known bias introduced into the intervention order assignment (the primary goal of random assignment).

Evaluation of the impact of the intervention was also limited by tracking the response of children with lower oral language alone and not monitoring the longer term impact of the intervention.

Conclusion

Structured phonological awareness and vocabulary instruction, set within the context of a quality children’s story book and culturally relevant activities proved effective in accelerating these skills in 5 year-old children who entered school with lower levels of oral language ability. With appropriate supports, class teachers implemented the intervention successfully resulting in the children’s word decoding abilities improving to a significantly greater extent than when teachers implemented the regular class literacy curriculum. The findings are promising in understanding how we can better support early literacy success from school entry for children with known challenges for their literacy learning. The longer term benefits and cost effectiveness of such interventions requires exploration in future studies.

References

A Better Start. (2015–2024). 10 Year national science challenge: Successful literacy and learning theme. Retrieved from http://www.abetterstart.nz.

Aaron, P. G., Joshi, R. M., Gooden, R., & Bentum, K. E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading: An alternative to the discrepancy model of LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41, 67–84.

Al Otaiba, S., Puranik, C. S., Ziolkowski, R. A., & Montgomery, T. M. (2009). Effectiveness of early phonological awareness interventions for students with speech or language impairments. The Journal of Special Education, 43, 107–128.

Aram, D. M., Ekelman, B. L., & Nation, J. E. (1984). Preschoolers with language disorders—10 years later. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 27, 232–244.

Billard, C., Bricout, L., Ducot, B., Richard, G., Ziegler, J., & Fluss, J. (2010). Reading, spelling and comprehension level in low socioeconomic backgrounds: Outcome and predictive factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 101–110.

Buckingham, J., Beaman, R., & Wheldall, K. (2014). Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The early years. Educational Review, 66, 428–446.

Cain, K., & Oakhill, J. (2014). Reading comprehension and vocabulary: Is vocabulary more important for some aspects of comprehension? Annee Psychologique, 114, 647–662.

Calder, H. (1992). Reading freedom teacher’s manual. Leichhardt: Pascal Press.

Carson, K., & Bayetto, A. (2018). Teachers’ phonological awareness assessment practices, self-reported knowledge and actual. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43, 67–85.

Carson, K., Gillon, G., & Boustead, T. (2011). Computer-administrated versus paper-based assessment of school-entry phonological awareness ability. Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing, 14(2), 85–101.

Carson, K. L., Gillon, G. T., & Boustead, T. M. (2013). Classroom phonological awareness instruction and literacy outcomes in the first year of school. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 44, 147–160.

Catts, H. W., Adlof, S. M., & Weismer, S. E. (2006). Language deficits in poor comprehenders: A case for the simple view of reading. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 49, 278–293.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Zhang, X. Y., & Tomblin, J. B. (2001). Estimating the risk of future reading difficulties in kindergarten children: A research-based model and its clinical implementation. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 38–50.

Chapman, J. W., Tunmer, W. E., & Prochnow, J. E. (2000). Early reading-related skills and performance, reading self-concept, and the development of academic self-concept: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 703–708.

Cirrin, F. M., Schooling, T. L., Nelson, N. W., Diehl, S. F., Flynn, P. F., Staskowski, M., et al. (2010). Evidence-based systematic review: Effects of different service delivery models on communication outcomes for elementary school-age children. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 41, 233–264.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33, 934–945.

Dietrichson, J., Bog, M., Filges, T., & Jorgensen, A. M. K. (2017). Academic interventions for elementary and middle school students with low socioeconomic status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 87, 243–282.

Dodd, B., Huo, Z., Crosbie, S., Holm, A., & Ozanne, A. (2006). Diagnostic evaluation of articulation and phonology. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., Boden, J. M., & Mulder, R. T. (2014). Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. Jama Psychiatry, 71, 1025–1031.

Fok, C. C. T., Henry, D., & Allen, J. (2015). Research designs for intervention research with small samples ii: stepped wedge and interrupted time-series designs. Prevention Science, 16, 967–977.

Foster, M. A., Lambert, R., Abbott-Shim, M., McCarty, F., & Franze, S. (2005). A model of home learning environment and social risk factors in relation to children’s emergent literacy and social outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20, 13–36.

Gillon, G. T. (2000). The efficacy of phonological awareness intervention for children with spoken language impairment. Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools, 31, 126–141.

Gillon, G. T. (2005). Facilitating phoneme awareness development in 3- and 4-year-old children with speech impairment. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 36, 308–324.

Gillon, G. T. (2018). Phonological awareness: From research to practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Gillon, G. T., & Macfarlane, A. H. (2017). A culturally responsive framework for enhancing phonological awareness development in children with speech and language impairment. Speech, Language and Hearing, 20, 163–173.

Gillon, G. T., Moran, C. A., Hamilton, E., Zens, N., Bayne, G., & Smith, D. (2007). Phonological awareness treatment effects for children from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Asia Pacific Journal of Speech Language and Hearing, 10, 123–140.

Gomez, C. J., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). Earthquake effects: Estimating the relationship between exposure to the 2010 chilean earthquake and preschool children’s early cognitive and executive function skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 127–136.

Good, R. H., & Kaminski, R. A. (2002). Dynamic indicators of basic early literacy skills (6th ed.). Eugene, OR: Institute for the Development of Education Achievement.

Gough, P., & Tunmer, W. (1986). Decoding, reading and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6–10.

Grimm, R. P., Solari, E. J., & Gerber, M. M. (2018). A longitudinal investigation of reading development from kindergarten to grade eight in a Spanish-speaking bilingual population. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 31, 559–581.

Hoover, W., & Gough, P. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2, 127–160.

Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2013). Learning to read: What we know and what we need to understand better. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 1–5.

Johnson, C. J., Beitchman, J. H., & Brownlie, E. B. (2010). Twenty-year follow-up of children with and without speech-language impairments: Family, educational, occupational, and quality of life outcomes. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 51–65.

Justice, L. M., Meier, J., & Walpole, S. (2005). Learning new words from storybooks: An efficacy study with at-risk kindergartners. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 36, 17–32.

Law, J., Rush, R., Schoon, I., & Parsons, S. (2009). Modeling developmental language difficulties from school entry into adulthood: Literacy, mental health, and employment outcomes. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 52, 1401–1416.

Liberty, K., Tarren-Sweeney, M., Macfarlane, S., Basu, A., & Reid, J. (2016). Behavior problems and post-traumatic stress symptoms in children beginning school: A comparison of pre- and post-earthquake groups. PLOS Currents Disasters. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.2821c82fbc27d0c2aa9e00cff532b402.

Macfarlane, S., Clarke, T., & Macfarlane, A. (2016). Language, literacy, identity and culture: Challenges and responses for Indigenous Māori learners. In L. Peer & G. Reid (Eds.), Multilingualism, literacy and dyslexia: Breaking down barriers for educators (2nd ed.). Oxford: Routledge.

Marulis, L. M., & Neuman, S. B. (2013). How vocabulary interventions affect young children at risk: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 6, 223–262.

McArthur, G., Castles, A., Kohnen, S., & Banales, E. (2016). Low self-concept in poor readers: Prevalence, heterogeneity, and risk. PeerJ 4, e2669. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2669.

McNeill, B. C., Gillon, G. T., & Dodd, B. (2009). Effectiveness of an integrated phonological awareness approach for children with childhood apraxia of speech (CAS). Child Language Teaching & Therapy, 25, 341–366.

Moats, L. (2009). Knowledge foundations for teaching reading and spelling. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 22, 379–399.

Moll, K., Ramus, F., Bartling, J., Bruder, J., Kunze, S., Neuhoff, N., et al. (2014). Cognitive mechanisms underlying reading and spelling development in five European orthographies. Learning and Instruction, 29, 65–77.

Morgan, P. L., Fuchs, D., Compton, D. L., Cordray, D. S., & Fuchs, L. S. (2008). Does early reading failure decrease children’s reading motivation? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(5), 387–404.

Morrison, Y. (2004). Down in the forest. Auckland: Scholastic.

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2017). Progress in international reading literacy study, PIRLS 2016 international results in reading.

Nancollis, A., Lawrie, B.-A., & Dodd, B. (2005). Phonological awareness intervention and the acquisition of literacy skills in children from deprived social backgrounds. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36, 325–335.

Nation, K., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Beyond phonological skills: Broader language skills contribute to the development of reading. Journal of Research in Reading, 27, 342–356.

O’Leary, P., Cockburn, M., Powell, D., & Diamond, K. (2010). Head start teachers’ views of phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge instruction. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38, 187–195.

Perfetti, C., & Stafura, J. (2014). Word knowledge in a theory of reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18, 22–37.

Reading Recovery New Zealand. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.readingrecovery.ac.nz/. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Russell, G., Ukoumunne, O. C., Ryder, D., Golding, J., & Norwich, B. (2018). Predictors of word-reading ability in 7-year-olds: Analysis of data from a UK cohort study. Journal of Research in Reading, 41, 58–78.

Schluter, P. J., Audas, R., Kokaua, J., McNeill, B., Taylor, B., Milne, B., & Gillon, G. (2018). The efficacy of preschool developmental indicators as a screen for early primary school-based literacy interventions. Child Development (in press). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13145.

Semel, E. M., Wiig, E. H., & Secord, W. A. (2006). Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals (4th-Australian Standardised Edition). Marrickville, NSW: Harcourt Assessment.

Share, D. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: Sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55, 151–218.

Snowling, M. J., Duff, F. J., Nash, H. M., & Hulme, C. (2016). Language profiles and literacy outcomes of children with resolving, emerging, or persisting language impairments. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57, 1360–1369. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12497.

Statistics New Zealand, T. A. (2017). Integrated Data Infrastructure. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/integrated-data-infrastructure.aspx. Accessed 14 Aug 2018.

Stoeckel, R. E., Colligan, R. C., Barbaresi, W. J., Weaver, A. L., Killian, J. M., & Katusic, S. K. (2013). Early speech-language impairment and risk for written language disorder: A population-based study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 34, 38–44.

Swanson, E., Stevens, E. A., Scammacca, N. K., Capin, P., Stewart, A. A., & Austin, C. R. (2017). The impact of tier 1 reading instruction on reading outcomes for students in grades 4–12: A meta-analysis. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30, 1639–1665.

Throneburg, R. N., Calvert, L. K., Sturm, J. J., Paramboukas, A. A., & Paul, P. J. (2000). A comparison of service delivery models: Effects on curricular vocabulary skills in the school setting. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 10–20.

Torppa, M., Georgiou, G. K., Lerkkanen, M. K., Niemi, P., Poikkeus, A. M., & Nurmi, J. E. (2016). Examining the simple view of reading in a transparent orthography: A longitudinal study from kindergarten to grade 3. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly-Journal of Developmental Psychology, 62, 179–206.

Tunmer, W., & Chapman, J. (2012). Does set for variability mediate the influence of vocabulary knowledge on the development of word recognition skills? Scientific Studies of Reading, 16, 122–140.

Tunmer, W., & Chapman, J. (2015). The development of New Zealand’s national literacy strategy. In W. Tunmer & J. Chapman (Eds.), Excellence and equity in literacy education. The case of New Zealand. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wake, M., Tobin, S., Levickis, P., Gold, L., Ukoumunne, O. C., Zens, N., et al. (2013). Randomized trial of a population-based, home-delivered intervention for preschool language delay. Pediatrics, 132, E895–E904.

Wamba, N. G. (2010). Poverty and literacy: An introduction. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 26, 109–114.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the children and their teachers who participated in this study. The authors would also like to acknowledge leaders and speech-language therapists within the Christchurch Ministry of Education who supported this project. This project was funded by the New Zealand Ministry of Education Business Innovation and Employment as part of the Better Start National Science Challenge Research program.

Funding

Funding was provided by Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (NZ) (Grant Number 15-02688).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A. et al. A better start to literacy learning: findings from a teacher-implemented intervention in children’s first year at school. Read Writ 32, 1989–2012 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9933-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9933-7