Abstract

L1 and L2 writers attend to different aspects of the formulation subprocess of writing. L2 writers devote more time and attention to low-level aspects such as grammar correction and spelling (Barbier 1998; Fagan and Hayden 1988; Whalen and Ménard 1995), leading to better spelling performances than L1 writers (Gunnarsson-Largy 2013). In deep-orthography languages such as French or English, L1 writers retrieve a phonological form of the word and then tend to automatically transcribe the most frequent corresponding orthographic form, whereas L2 writers seem to directly retrieve the exact orthographic form. For L2 writers, the visuo-orthographic form of the word therefore seems to prevail over the phonological one. Accordingly, we hypothesized that L1 and L2 writers rely differently on working memory (WM). To test this hypothesis, we designed an experiment where two groups (Levels B1 and C1) of instructed L2 French learners and an L1 French control group wrote dictated sentences, with compulsory negation marking in an ambiguous phonological context. While writing, they performed a concurrent task that induced a cognitive load on either phonological or visual WM, in order to identify the nature of the form maintained in WM during semantic checking. Results indicated that L2 French learners gradually move from a visual to a more phonological form of retrieval.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For reasons of clarity and coherence, we chose to use Levelt’s terminology to identify the writing subprocesses. Kellogg refers to them as planning (conceptualization), translating (formulation), execution (graphic transcription) and monitoring (revision).

In several studies, Pacton and colleagues showed similar implicit learning of graphotactic patterns in L1 French children learning to write (see, for example, Pacton, Sobaco, Fayol, & Treiman, 2013).

Adult writers rely on automatisms to deal with spelling and grammar (low-level aspects) in L1. For French writers, one of these automatisms is making the verb agree with the noun that directly precedes it. When adult writers have to transcribe sentences where the subject is followed by another noun in another number, the verb is incorrectly made to agree with the second noun [*Le père (sing.) des enfants (pl.) jouent au football]. This kind of error can be observed in corpus studies, and has been studied in an experimental paradigm where cognitive overload is induced by a concurrent task (Fayol, Largy, & Lemaire, 1994). Largy, Fayol, and Lemaire (1996) also showed that when cognitive overload is induced, adult writers (experts) automatically retrieve the most frequent form of a word when this word has homophones.

The levels of the students were established by several placement tests (written and oral comprehension, grammar and written production) at the beginning of the university year. As a result of these tests, they were placed in corresponding course levels.

Besides English, some participants had also learned Spanish (5) or German (3).

In nonambiguous contexts in oral French (not the case in the present study) when the subject is a clitic pronoun, the ne in the negation is often omitted. However, when the subject is a nonclitic pronoun or lexical noun phrase, the ne is produced more often than has been suggested in previous research (Meisner, 2010).

As the scores for the dependent variable were percentages calculated on four sentences per context, the medians in two groups could potentially be the same, even when the distribution was different and the nonparametric tests showed a significant difference.

As recommended by one of our anonymous reviewers, we provide the results of all the correlation analyses for the EC condition and the concurrent tasks, including those for which the results of Analyses 1 and 2 were not significant (see Table 16 in the Appendix).

Frequency checked using Google (French-language sites) on 30 October 2017: on a = 19,610,000,000 hits and on n’a = 743,000,000 hits.

The most common learning situation these days for L2 learners in Western countries is probably instructed learning (Housen & Pierrard, 2005).

References

Audacity Team. (2015). Audacity(R): Free audio editor and recorder [computer application]. Version 2.1.1. Retrieved from https://audacityteam.org. Accessed 21 June 2016.

Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Working memory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Baddeley, A. D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(11), 417–423.

Baddeley, A. D. (2015). Working memory in second language learning. In Z. Wen, M. Borges Mota, & A. McNeill (Eds.), Working memory in second language acquisition and processing (pp. 17–28). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 8). New York: Academic Press.

Barbier, M.-L. (1998). Rédaction en langue première et en langue seconde: Comparaison de la gestion des processus et des ressources cognitives. Psychologie Française, 43(4), 361–370.

Bassetti, B. (2017). Orthography affects second language speech: Double letters and geminate production in English. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000417.

Bassetti, B., & Atkinson, N. (2015). Effects of orthographic forms on pronunciation in experienced instructed second language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36(01), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716414000435.

Bethell-Fox, C. E., & Shepard, R. N. (1988). Mental rotation: Effects of stimulus complexity and familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 14(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.14.1.12.

Brunner, E., Domhof, S., & Langer, F. (2002). Nonparametric analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experiments. New York, NY: Wiley.

Brunet, E. (2002). Mots les plus fréquents de la langue écrite française (XIXe et XXe siècles). Retrieved from http://eduscol.education.fr/cid47916/liste-des-mots-classee-par-frequence-decroissante.html. Accessed 1 Sept 2016.

Buetler, K. A., de León Rodríguez, D., Laganaro, M., Müri, R., Nyffeler, T., Spierer, L., et al. (2015). Balanced bilinguals favor lexical processing in their opaque language and conversion system in their shallow language. Brain and Language, 150, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2015.10.001.

Buetler, K. A., de León Rodríguez, D., Laganaro, M., Müri, R., Spierer, L., & Annoni, J.-M. (2014). Language context modulates reading route: An electrical neuroimaging study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00083.

Cook, V. J. (1997). L2 users and English spelling. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 18(6), 474–488.

Cutler, A., Treiman, R., & van Ooijen, B. (2010). Strategic deployment of orthographic knowledge in phoneme detection. Language and Speech, 53(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830910371445.

Delattre, P. (1947). La liaison en français, tendances et classification. The French Review, 21(2), 148–157.

De Neys, W. (2006). Automatic–heuristic and executive–analytic processing during reasoning: Chronometric and dual-task considerations. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59(6), 1070–1100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724980543000123.

Dherbey, N., & Gunnarsson-Largy, C. (in review). Categorisation of L2 phonemes induces a cognitive load. Second Language Research.

Dijkstra, T., Roelofs, A., & Fieuws, S. (1995). Orthographic effects on phoneme monitoring. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49, 264–271.

Durand, J., & Lyche, C. (2008). French liaison in the light of corpus data. Journal of French Language Studies, 18(01). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959269507003158.

Escudero, P., & Wanrooij, K. (2010). The effect of L1 orthography on non-native vowel perception. Language and Speech, 53(3), 343–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830910371447.

Fagan, W. T., & Hayden, H. M. (1988). Writing processes in French and English of fifth grade immersion students. Canadian Modern Language Review, 44(4), 653–668.

Fay, M. P., & Proschan, M. A. (2010). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney or t-test? On assumptions for hypothesis tests and multiple interpretations of decision rules. Statistics Surveys, 4, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-SS051.

Fayol, M. (1997). Des idées au texte: psychologie cognitive de la production verbale, orale et écrite. Paris: Presses Univ. de France.

Fayol, M., Largy, P., & Lemaire, P. (1994). When cognitive overload enhances subject-verb agreement errors. A study in French written language. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 47A, 437–464.

Gathercole, S. E., & Baddeley, A. D. (1993). Working memory and language. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gaudron, J.-P. (2016). R commander: Petit guide pratique 1. Statistiques de base. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/other-docs.html#nenglish.

Gunnarsson-Largy, C. (2013). Utiliser l’erreur pour détecter les automatismes et l’expertise en production écrite en FLE. In C. Gunnarsson-Largy & E. Auriac-Slusarczyk (Eds.), Ecriture et réécriture chez les élèves : Un seul corpus, divers genres discursifs et méthodologies d’analyse (pp. 287–302). Louvain-la-Neuve: Academia.

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework of understanding cognition and affect in writing. In C. Michael Levy & Sarah Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing (pp. 1–27). Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1980). Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L. W. Gregg & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 3–30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hayes-Harb, R., Nicol, J., & Barker, J. (2010). Learning the phonological forms of new words: Effects of orthographic and auditory input. Language and Speech, 53(3), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830910371460.

Housen, A., & Pierrard, M. (2005). Investigating instructed second language. In A. Housen & M. Pierrard (Eds.), Investigations in instructed second language acquisition (pp. 1–27). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Jakimik, J., Cole, R. A., & Rudnicky, A. I. (1985). Sound and spelling in spoken word recognition. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behaviour, 24, 165–178.

Katz, L., & Feldman, L. B. (1983). Relation between pronunciation and recognition of printed words in deep and shallow orthographies. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 9, 157–166.

Katz, L., & Frost, R. (1992). The reading process is different for different orthographies: The orthographic depth hypothesis. Amsterdam: Elsevier North Holland Press.

Kellogg, R. T. (1996). A model of working memory in writing. In C. M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing (pp. 57–71). Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum.

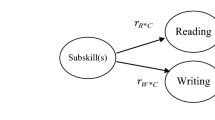

Kellogg, R. T., Olive, T., & Piolat, A. (2007). Verbal, visual, and spatial working memory in written language production. Acta Psychologica, 124(3), 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2006.02.005.

Koda, K. (2012). Second language reading, scripts and orthographies. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), Encycolopedia of applied linguistics. Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken.

Largy, P. (2002). Apprentissage et mise en œuvre de la morphologie flexionnelle du nombre (Thèse d’habilitation à diriger la recherche). Rouen: Université de Rouen.

Largy, P., Fayol, M., & Lemaire, P. (1996). The homophone effect in written French: The case of verb-noun inflection errors. Language and Cognitive Processes, 11(3), 217–255.

Le Bigot, N., Passerault, J.-M., & Olive, T. (2012). Visuospatial processing in memory for word location in writing. Experimental Psychology, 59(3), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000136.

Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Martin, K. I. (2017). The impact of L1 writing system on ESL knowledge of vowel and consonant spellings. Reading and Writing, 30(2), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-016-9673-5.

Meisner, C. (2010). A corpus analysis of intra- and extralinguistic factors triggering ne -deletion in phonic French. In Congrès Mondial de Linguistique Française - CMLF 2010 (pp. 1943–1962). Paris: Institut de Linguistique Française. https://doi.org/10.1051/cmlf/2010091.

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Rettinger, D. A., Shah, P., & Hegarty, M. (2001). How are visuospatial working memory, executive functioning, and spatial abilities related? A latent-variable analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(4), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1037//0096-3445.130.4.621.

Muneaux, M., & Ziegler, J. (2004). Locus of orthographic effects in spoken word recognition: Novel insights from the neighbour generation task. Language and Cognitive Processes, 19(5), 641–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690960444000052.

New, B., & Pallier, C. (2001). Gougenheim 2.0. Retrieved from http://www.lexique.org/public/gougenheim.php. Accessed 1 Sept 2016.

Oberauer, K., & Lange, E. B. (2008). Interference in verbal working memory: Distinguishing similarity-based confusion, feature overwriting, and feature migration. Journal of Memory and Language, 58(3), 730–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.09.006.

Olive, T., Kellogg, R. T., & Piolat, A. (2008). Verbal, visual, and spatial working memory demands during text composition. Applied Psycholinguistics. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716408080284.

Ota, M., Hartsuiker, R. J., & Haywood, S. L. (2010). Is a FAN Always FUN? Phonological and orthographic effects in bilingual visual word recognition. Language and Speech, 53(3), 383–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830910371462.

Pacton, S., Sobaco, A., Fayol, M., & Treiman, R. (2013). How does graphotactic knowledge influence children’s learning of new spellings? Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00701.

Pattamadilok, C., Morais, J., Colin, C., & Kolinsky, R. (2014). Unattentive speech processing is influenced by orthographic knowledge: Evidence from mismatch negativity. Brain and Language, 137, 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2014.08.005.

Peereman, R., Dufour, S., & Burt, J. S. (2009). Orthographic influences in spoken word recognition: The consistency effect in semantic and gender categorization tasks. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(2), 363–368. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.16.2.363.

Rapp, B., Epstein, C., & Tainturier, M.-J. (2002). The integration of information across lexical and sublexical processes in spelling. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 19(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264329014300060.

Rapp, B., Purcell, J., Hillis, A. E., Capasso, R., & Miceli, G. (2016). Neural bases of orthographic long-term memory and working memory in dysgraphia. Brain, 139(2), 588–604. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv348.

Rastle, K., McCormick, S. F., Bayliss, L., & Davis, C. J. (2011). Orthography influences the perception and production of speech. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37(6), 1588–1594. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024833.

Shea, C. (2017). L1 English/L2 Spanish: Orthography–phonology activation without contrasts. Second Language Research, 33(2), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658316684905.

Shelton, J. R., & Caramazza, A. (1999). Deficits in lexical and semantic processing: Implications for modes of normal language. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 6, 5–28.

Shelton, J. R., & Weinrich, M. (1997). Further evidence of a dissociation between output phonological and orthographic lexicons: A case study. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 14(1), 105–129.

Slowiaczek, L. M., Soltano, E. G., Wieting, S. J., & Bishop, K. L. (2003). An investigation of phonology and orthography in spoken-word recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 56A, 233–262.

Vallar, G., & Baddeley, A. D. (1984). Phonological short-term store, phonological processing, and sentence comprehension: A neuropsychological case study. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 1, 121–141.

van Berkel, A. (2004). Learning to spell in English as a second language. IRAL - International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2004.012.

Wang, S., & Allen, R. J. (2018). Cross-modal working memory binding and word recognition skills: How specific is the link? Memory, 26(4), 514–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2017.1380835.

Wang, W., & Wen, Q. (2002). L1 use in the L2 composing process: An exploratory study of 16 Chinese EFL writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 11(3), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(02)00084-X.

Wauquier-Gravelines, S. (1996). Organisation phonologique et traitement de la parole continue [Phonological organization and connected-speech processing]. Paris: Université Paris 7.

Whalen, K., & Ménard, N. (1995). L1 and L2 writers’ strategic and linguistic knowledge: A model of multiple-level discourse processing. Language Learning, 45(3), 381–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1995.tb00447.x.

Ziegler, J. C., & Ferrand, L. (1998). Orthography shapes the perception of speech: The consistency effect in auditory word recognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 5, 683–689.

Ziegler, J. C., Ferrand, L., & Montant, M. (2004). Visual phonology: The effects of orthographic consistency on different auditory word recognition tasks. Memory & Cognition, 32(5), 732–741.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gunnarsson-Largy, C., Dherbey, N. & Largy, P. How do L2 learners and L1 writers differ in their reliance on working memory during the formulation subprocess?. Read Writ 32, 2083–2110 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-019-09941-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-019-09941-y